Access to clear, reliable, re-usable community resource directory data is not just important for people who are seeking services that meet their immediate needs — it’s also crucial for people who are seeking to understand the workings of the human service system as a whole, as they seek ways improve health and wellness for entire communities.

Bread for the City — the primary community anchor institution for the first Open Referral pilot, DC Open211 — is already demonstrating the potential for resource data to spark systemic changes that tangibly improve the lives of their clients and the health of their community.

I’ve just reported on this story over at the Huffington Post. Here’s the gist:

For years, Bread for the City’s social workers have been disturbed by the tendency of other food pantries in the D.C. metro area to require third-party referrals. They observed that many of their ‘walk-ins’ had been instructed to come to Bread for the City by other organizations who required a signed document from a third-party to serve as ‘proof of need.’ The social workers knew that these referral policies created more work for them — and, even worse, they posed a major unnecessary cost in money, time, and dignity for their clients.

Bread for the City has recently been revamping their intake and referral systems, and with newly-interoperable systems in place they can now easily gather hard data about this problem. The result is striking:

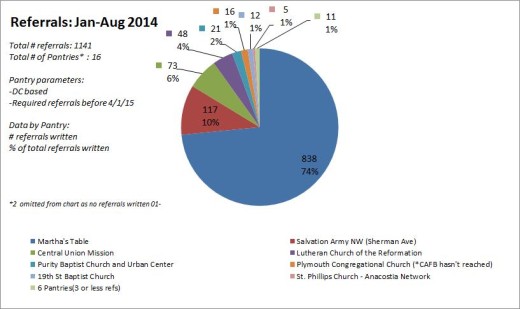

Thanks to an upgrade in their case management technology, Bread [for the City]’s social workers are now able to analyze their referral patterns over time. The records show that from January to August of last year, Bread for the City wrote over 1,141 individual paper referrals to other organizations. More analysis revealed that almost all of these referrals could be traced back to the same 14 food pantries.

Bread for the City estimates that the paper referral policy costs $20 per person per trip, factoring in public transportation and time away from work to make this additional journey. (No one knows how many people just get discouraged and go without help.)

Furthermore, Bread for the City’s social workers found that almost half of their ‘walk-ins’ were solely seeking referrals elsewhere — a major burden on the organization’s own workload.

Now that they had hard data about this problem, Bread for the City started talking to people about it. First, they organized meetings with clients to learn more about their first-hand experiences with referral processes, and to solicit their suggestions for improvements.

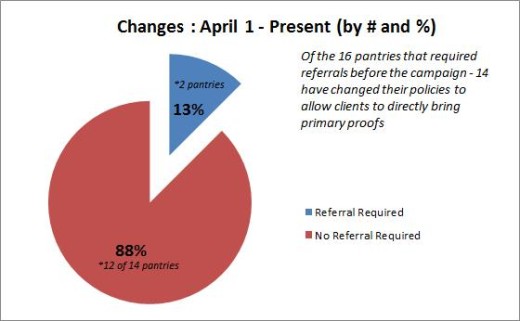

Then Bread for the City engaged the Capital Area Food Bank. This partnership proved essential because because 12 of the 14 organizations already had a relationship with the Food Bank. This created trust amongst all of the partners, which made it much easier to reach an agreement around new policy changes at the organizations that previously required referrals for food assistance.

Thus far, 12 of the partner organizations have agreed to drop their referral requirements. These pantries represented 88 percent of the referrals Bread for the City wrote during the period under review.

Kathleen Stephan is Bread for the City’s community resource coordinator, and she has also served as one of the and one of the active participants in our Open Referral pilot in DC. At Bread for the City’s blog, Kathleen wrote about the critical analysis that drove this work:

[W]e are thinking a lot about racial equity at BFC. We are challenging ourselves as service providers to consider how we are perpetuating oppression and racism – in our own programs and also in the larger systems that we work within. Historically, social service provision has often been based on antiquated ideas of worthy and unworthy poor. We believe the elimination of paper referrals is an important shift away from a prejudiced charity model.

In this way, Bread for the City is demonstrating the importance of Open Referral’s conceptual framework, in which the perspectives of multiple types of users have generated the Initiative’s critical design parameters. Obviously, people seeking help and people providing help are critical users, but community resource data is also used by people who are researching and analyzing the effectiveness of human services broadly. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about BFC’s story is that these different ‘user personas’ — of help-seeker, service providers, and researcher/analyst — aren’t all either/or categories.

In fact, service providers and even help seekers might also act as researchers too, in which case resource directory data is essential to their ability to analyze systemic problems and advocate for changes in their community. The promotion of people’s ability to use the same data for multiple purposes might be one of the most transformative effects of the Open Referral initiative.

This is precisely the kind of systemic change that we’ve always envisioned could be made possible in the long-run by projects like DC Open211. Kudos to Bread for the City for making such change happen right now.

Leave a Reply