Last year – with sponsorship from Robert Wood Johnson Foundations’ DASH program, and in partnership with Paul Sorenson at the Regional Data Alliance at University of Missouri St Louis (UMSL) – I co-authored a whitepaper that aggregated research and recommendations from across the emerging field of “social care coordination.”

This paper provides a strategic framework in which to understand Open Referral’s work in the context of human service directory data infrastructure and governance, and it also offers a broader view of the related but very different challenges of sharing information about people through coordination among service providers.

The whitepaper is available in PDF here – as well as in this ‘live’ version upon which we invite readers to share feedback. Having received significant positive feedback from experts in the field of healthcare informatics, I’m excited to share it here with the Open Referral community.

First, some background:

Open Referral has a (relatively) narrow scope within the vast field of human service informatics

The name “Open Referral” sometimes causes confusion: people incorrectly assume we deal with processes involved in making referrals from one provider to another!

But when we first launched this initiative (eight years ago! ?) we did so in dialogue with stakeholders in the field of ‘Information-and-Referral’ – known as “I&R” – a mature industry primarily comprised of call centers that manage community resource databases, in which these I&R providers aggregate information about services to which people can be ‘referred.’

Open Referral formed with a focus on the ‘information’ piece of this puzzle – aiming to shift the field of I&R toward “open” models of information stewardship, such that the data available in community resource databases ought to be freely usable by any channel through which a person might be referred (or might refer themselves) to a service.

We decided from the beginning that we wouldn’t address the actual mechanics of making a ‘referral’; we believed that directory information about social services should be freely available for people to use in any number of ways, such as making referrals of any kind, and that was about the extent of it.

The field of human service informatics is rapidly evolving through attempts to establish interoperability for sensitive personal data

In the years since Open Referral launched, the concept of “referral” has changed in front of our eyes. Conventionally, “making a referral” (in the context of social service referral providers) has typically involved providing information about services to people seeking help, in support of their self-directed action. Many new initiatives in this space, however, are motivated by the objective of making “warm” referrals, through which providers share information about people with other providers. In this context, providers become more actively involved in coordination of care for people (i.e. clients, in social service contexts, or patients in healthcare contexts), help-seekers can get more support in the process of accessing multiple services to meet complex needs, and providers can get insight into the results of these activities in the form of feedback about the outcome of the referral – shared from the referred-to provider back to the referrer – known as ‘closing the loop’.

2-1-1 San Diego first demonstrated the means of enabling this kind of “warm referrals” and “closed loop” at a large scale – across multiple organizations and different technologies throughout a region – with their Community Information Exchange (i.e., CIE). Through the San Diego CIE, service providers can make “warm referrals” with “closed loops” for their clients across organizations using different technologies – an impressive achievement that took years of development and millions of dollars in funding. (Their toolkit is a good starting point for learning about this.)

In the years since, a large and rapidly evolving field has emerged in association with this concept of CIEs. Most of Open Referral’s I&R partners, especially in the U.S., are now involved one way or another in discussions or active plans to build a CIE. Open Referral’s scope remains fixed narrowly on the matter of resource directory data; of course, resource data is one of the building blocks of a CIE, and Open Referral’s data standards can expand the range of options and lower the various costs associated with setting such building blocks into place.

More importantly, some of the principles and practices applied in Open Referral may also be relevant for the very different set of challenges involved in sharing information about people across many technologies and institutional contexts.

Exchange of data about people poses a whole other set of challenges compared with resource directory data – but some of the same principles still apply

In 2020, the DASH program invited Open Referral’s leadership (hi ?) to partner with the RDA at UM-StL in assessing the set of technology challenges associated with Community Information Exchange. In addition to a literature review and a case study conducted there in St Louis, our paper draws upon learnings from dozens of community initiatives involved in the Open Referral network and/or the Gravity Project, in which I am a strategic advisor on community resources and engagement.

Our first finding was that there is a misconception – common among many current would-be CIE initiatives – that “community information exchange” is something that can be effectively enabled by a single centralized software system that all service providers would presumably be enticed to start using. Yet while “a single software system that everyone uses” sounds like an appealing solution at a distance, reality is just not so simple. Different kinds of organizations providing different kinds of services in different contexts have different needs; whereas software, if it is to be well-designed, must focus on the needs of specific kinds of users, and prioritize certain kinds of behavior over others. This means a single software system can’t equitably and effectively meet “all” of the needs in a community. We looked for examples to the contrary, but found no historical precedents for such a proposition (in this field, or any other really).

Instead of imagining that this complex problem can possibly have a single solution, we should assume that effective strategies will themselves be complex – with many different actors using various technologies working together to build capacities to coordinate across systems. Our paper describes a framework for thinking about these challenges, and offers an array of methods and guiding questions with which communities can cope with them.

Spoiler alert: we consistently find that the biggest challenges are not really about this or that functionality of this or that technology – but rather the contexts in which such technology is designed and in which decisions about its use are made. Overall, our strong recommendation is that – before making decisions about specific software and the various vendors thereof – communities ought to address questions about standards, the politics of infrastructure, and the processes of governance.

Summarizing the Data Dilemmas:

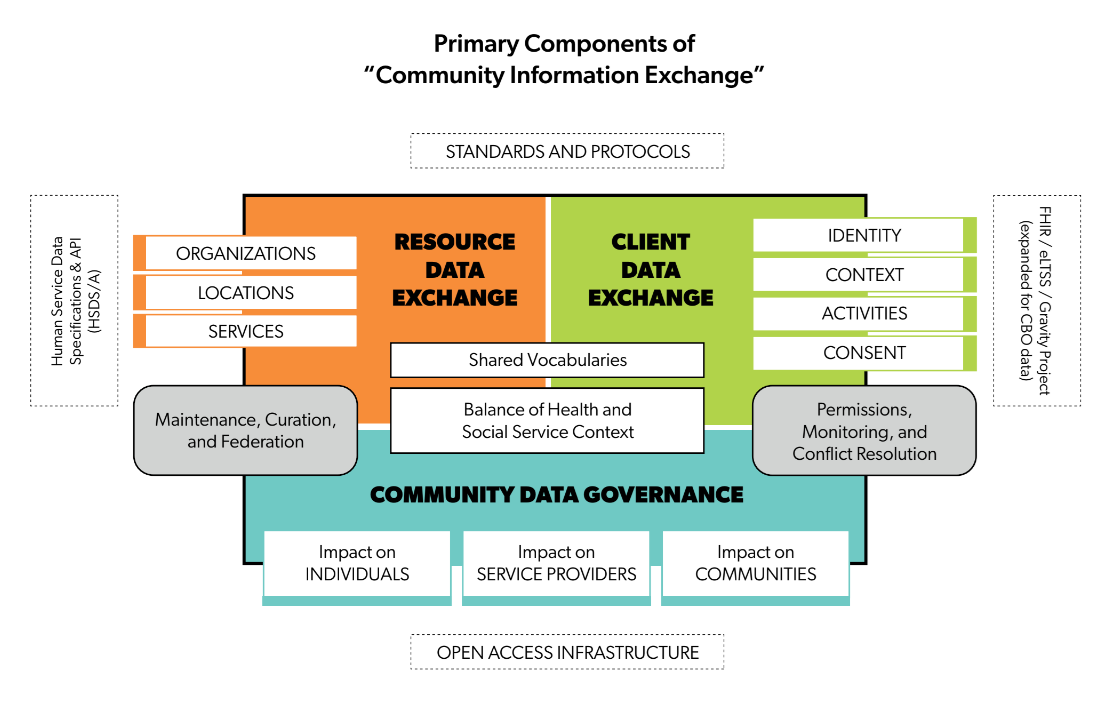

In the paper, we identify three kinds of capacities that seem to be essential to the concept of a “Community Information Exchange:

- the capacity to exchange information about resources

- the capacity to exchange information about people

- the capacities with which communities can govern all of the above

The first capacity – resource directory data infrastructure – is that which Open Referral helps develop. This section will be familiar to readers of Open Referral’s blog; here I’ll focus on summarizing the following sections.

The second capacity – personal data exchange infrastructure – is more or less the same capacity established among clinical systems by Health Information Exchanges (HIEs), and is currently being experimentally extended for use among human service providers by the Gravity Project through alignment of various clinical terminologies and development of HL7’s FHIR protocols.

The third capacity – governance – is alarmingly underdeveloped in almost all of the cases that we assessed.

Personal information exchange: related but distinct problems of varying difficulty

We identified four sets of challenges that need to be met in order to enable the necessary conditions for making a ‘warm referral’ of a client from one provider to another, and ‘closing the loop’ between these providers.

Identities – For someone at one organization using a given information system to share information about a client with another provider at a different organization using a different information system, each information system needs to be able to effectively recognize the same person. Established methods for identity-matching have made this an easier (though not fully solved) problem.

Context – To effectively coordinate care across organizations and technologies, clients and providers need to be able to understand each other despite differences in vocabularies. Through standardized terminologies to describe a person’s context (their needs, goals, and salient personal criteria) and the ability to translate between these terminologies. The divergence of vocabularies is one of humanity’s oldest dilemmas, but through efforts like the Gravity Project we can cope with these challenges by extending terminologies to address social circumstances, and aligning terminologies across sectors.

Activity – When things happen that are relevant to a person’s care (such as asking for help, applying for a program, receiving services, etc) how do we share information about such activities across different systems. Exchanging data across systems over time is a technical problem, one solved by a range of protocols for data exchange; most importantly, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has now mandated the use of such protocols – specifically, APIs that use HL7’s FHIR framework – as a policy requirement for all health plans. With efforts such as Gravity’s to extend the FHIR framework to recognize contextual terminologies from social care sectors, this capacity can now be built among human service providers as well.

Consent – As far as I can see, this challenge – that of consentful, ethical data collection and exchange – is the problem that is least ‘solvable’ by technology and most demands our attention. As someone who constantly thinks about digital justice, while also constantly giving consent for data about me to be collected and used by many different entities (some of whom I don’t particularly trust), I believe we ought to be concerned about even the best possible outcomes of current efforts to establish “human-centered,” “HIPAA compliant” consent processes that are “frictionless” and “scalable.” We outline a range of issues in the paper that demand solutions involving actors who are neither technologists or lawyers. For now, I’ll just point readers to the Consentful Tech project and Sean McDonald’s writing about the insufficiency of individual consent as a model for ethical management of data collection and use.

Governance: the most important subject of our attention

The key point of the paper is that the problems associated with “Community Information Exchange” are not, first and foremost, problems of technology and data. These problems are primarily matters of power and accountability. People in this field often refer to “health equity” as their primary mission – but equity isn’t just something to which we can simply aspire through declaration, no moreso than we can call the design of a system “human-centered” because it’s portrayed in a diagram that has little icons of people in the middle.

All systems are governed, but only well-governed systems are equitable.

In the “Governance” section of the paper, we explore the range of considerations about governance that precede and extend beyond questions of “data governance” – such as how stakeholders are represented in an initiative to exchange data (which we call “institutional governance”) and how rules are made, enforced, arbitrated, and changed (which we call “administrative governance”).

We strongly recommend that all stakeholders in these processes put questions of governance first and foremost on their agenda, and invest the (human, local) capacities needed to equitably answer those questions.

Moving this work forward

We welcome more feedback on this paper! Please leave comments on the ‘live’ version, especially if you have a critical perspective that might push us to make the contents better.

I also want to invite any readers who are interested in discussing these topics to join an Affinity Group that I will facilitate, sponsored by the All In network with support from DASH, on the topic of “Reimagining Technology for Cross-Sector Care Coordination.” In this group, which kicks off on May 6th, we will discuss the components of this paper through peer-learning formats in monthly discussions throughout the summer. Learn more about the Affinity Group here, and reach out to the contacts listed therein to get involved.

Finally, if you want to work together to design equitable and effective strategies for social care data exchange in your community, reach out to discuss!

Leave a Reply