I’m excited to share with you this toolkit for information exchange initiatives that aim to address the social determinants of health – just recently released by the Office of the National Coordination for Health Information Technology at the US Department of Health and Human Services (known as ONC). The toolkit (PDF downloadable here) synthesizes subject matter expertise from across the health, human, and social service sectors to offer guidance on the design and implementation of initiatives to enable information exchange among healthcare and social care providers.

(Also of note: ONC also recently acknowledged Open Referral’s Human Service Data Specification as the industry standard for resource directory data exchange – see page 105 of their Interoperability Standards Advisory document.)

ONC’s new toolkit largely addresses issues beyond resource directory information, and yet it reflects many of the lessons learned and strategic objectives of the Open Referral initiative. It may be helpful for communities that are working to improve their supply chain for resource directory information – as well as communities for which resource directory information is just one piece of a more complex strategic goal. I’ll offer some background context:

Why this matters: building capacities for coordination of care across health and social sectors

In recent years, healthcare policymakers and institutions have become increasingly interested in strategies that can more effectively and equitably address the “social determinants of health” – in other words, the non-medical circumstances that affect people’s wellness. Such circumstances are often referred to by healthcare experts as “upstream” from clinical practice, which is to say that when illnesses present themselves in a doctor’s office or emergency room, their root causes can often be traced back to factors like structural racism, gender and sexuality biases, housing, food systems, and other inequitable societal patterns. As healthcare systems become more aware of the way these social factors determine clinical outcomes, they are increasingly motivated to develop strategies that can improve the capacities for healthcare and social care providers to coordinate care – especially for people who are at risk of health inequity.

Of course, such capacities for coordination of care involve the ability to exchange information among organizations in different sectors, using different technologies.

As readers of this blog know, that presents a big bunch of knotty problems!

Open Referral has already made great progress on one piece of this puzzle: information about the resources available to meet people’s needs. Beyond resource directory information, however, there are a whole thicket of challenges involved in the exchange of sensitive personal information – all technically outside of Open Referral’s scope. Nevertheless, as reported here in this blog before, we’ve had the opportunity to inform several initiatives that have developed guidance for policymakers and practitioners that are developing health and social care integration strategies, such as the Gravity Project, and Data Across Sectors for Health.

In 2021, I had the opportunity to work with EMI Advisors in support of ONC (which is kind of like the IT office for HHS) through facilitation of a “technical expert panel” of people – with backgrounds ranging from government to healthcare, social services, and philanthropy – selected to advise the government on the current state and future potential of the domain of information exchange among health and human service systems. We facilitated a series of discussions throughout the year, and synthesized a set of findings and recommended best practices that can guide policymakers, funders, practitioners and community leaders through the process of designing strategies to enable information exchange among previously-siloed organizations and technologies.

In 2022, we presented the results from this panel in a series of Learning Forums hosted by ONC and recorded for viewing here.

This past week, ONC has released the toolkit itself. I hope it can be helpful for those in the field who are charting challenging and uncertain courses toward a future in which healthcare and social care systems will more effectively and equitably meet people’s needs.

Assessing the state of the field: where are we and where do we want to go?

When we first convened to discuss this topic, I think it’s fair to say that the technical panel would be focused on, well, technical issues. But when we heard from people with experience in implementation in this field – as well as experts on information exchange in other fields – most of the salient issues were not primarily about technology.

Instead, we kept hearing questions about the relationship of an information exchange initiative to the communities whose information is being collected and whose interests are at stake. Through rounds of dialogue among panelists and relevant stakeholder representatives, we identified a range of common challenges and strategic patterns that primarily involved purpose (what is information exchange for?) and power (who decides what can, should, must, and must not happen?). Questions about technology did come up, of course – especially with regards to standards, interoperability infrastructure like APIs, and procurement policies – but by and large TEP members seemed to agree that the tools involved with information exchange are secondary or tertiary concerns. The primary questions are institutional.

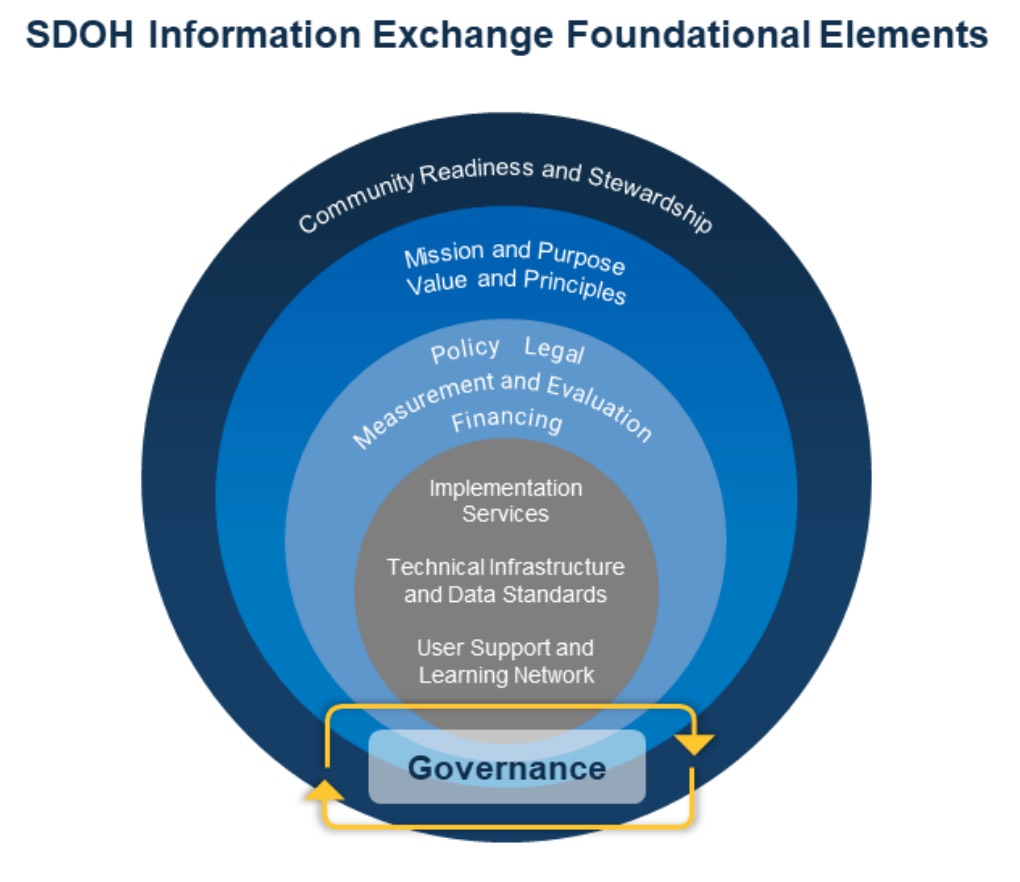

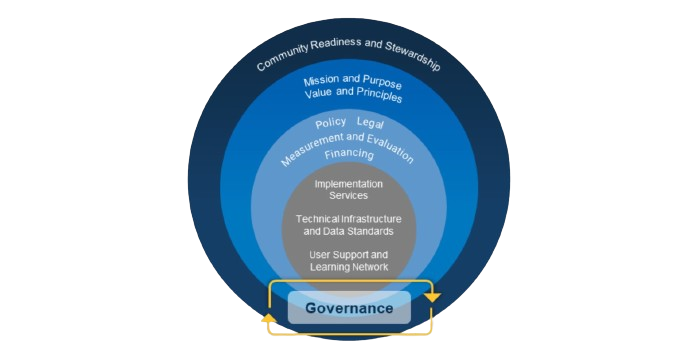

From this process, we articulated a set of “foundational elements” that one would expect to find in any effective and equitable initiative to facilitate information exchange among systems of health and social care. These foundational elements are visually presented here, and structure the contents of the toolkit accordingly.

As this diagram conveys, we found that questions about community are asked at the most fundamental level of any effective and equitable initiative to facilitate information exchange among systems of health and social care. Who is the initiative for, what do they need, and how will they be involved in its stewardship? We repeatedly heard that all other processes should follow from these questions. An initiative should have a clearly articulated mission and purpose, along with statements of values and principles, which reflect the prerogatives of the people whose interests are at stake. Only from the vantage point established by a community’s purpose and principles can other, more tactical questions be appropriately answered – such as questions about policy and legal frameworks, financing, measurement and evaluation, and finally implementation of technical infrastructure and provision of user support and learning systems.

Tying all of these elements together, of course, is governance. Questions about governance were some of the trickiest to emerge through the panel’s discussions. Some panel members understood governance to be a matter of ensuring regulatory compliance around data collection, management, and use. But other questions – about not just legal matters but also ethical matters and decision-making processes – made it clear that good governance entails more than just data governance. Governance of information exchange across sectors involves decisions about resource allocation, business models, and, ultimately, the rights of people and communities.

The toolkit offers this framework to describe a multi-layered approach to governance:

Institutional governance sets the terms of participation in an initiative, including the processes by which leadership and membership are organized, priorities are set and adjusted, rulemaking processes are established and changed, and institutional conflicts are resolved.

Administrative governance is the process of designing, monitoring, and enforcing policies – – as determined by institutional governance.

Finally data governance entails implementation and enforcement of rules for technical standards and data collection, management, storage, exchange, verification, validation, contestation, and deletion.

In other words, through data governance answers the question of how the rules pertaining to data will be applied; while administrative governance establishes how such rules are made; and institutional governance answers the question of who decides what rules there will be, and – crucially – who decides who decides.

Our subject matter experts made clear that these questions are more difficult to answer, and more important to get right, than questions about databases, software, and other technical matters.

To provide guidance across the board, the toolkit includes a set of definitions, challenges, opportunities, examples, best practices and additional resources.

Learning together in the ONC Learning Forums

As mentioned above, we presented findings from this process at a series of learning forums hosted by ONC – all of which are recorded and available to view here.

This series of Learning Forums has kicked off again in conjunction with the toolkit’s release. There will be three more Learning Forums in the coming months – you can register to attend now at the link above!

It takes a village

I’m grateful for the opportunity to have participated in this process: many thanks to EMI Advisors for driving this process, Karis Grounds at 211 San Diego’s Community Information Exchange for her co-facilitation and expertise, the TEP members for providing their insight and time, and ONC for initiating the process and sharing the results with the public now.

I’ve already been putting the contents of this toolkit to work! A range of communities across the country are in the midst of designing “community information exchange” strategies, and I find that the framework of foundational elements described in this toolkit – and the resources included – help engender productive and careful strategic planning among networks of health, human, and social service providers, policymakers, and funders. Reach out to learn more about this emerging practice and how Open Referral might help your community!

Leave a Reply