Early last month, I traveled to Madrid to discuss the community resource directory data problem, and our work here in the Open Referral initiative, at the commencement of a civic hacking workshop hosted by Medialab-Prado.

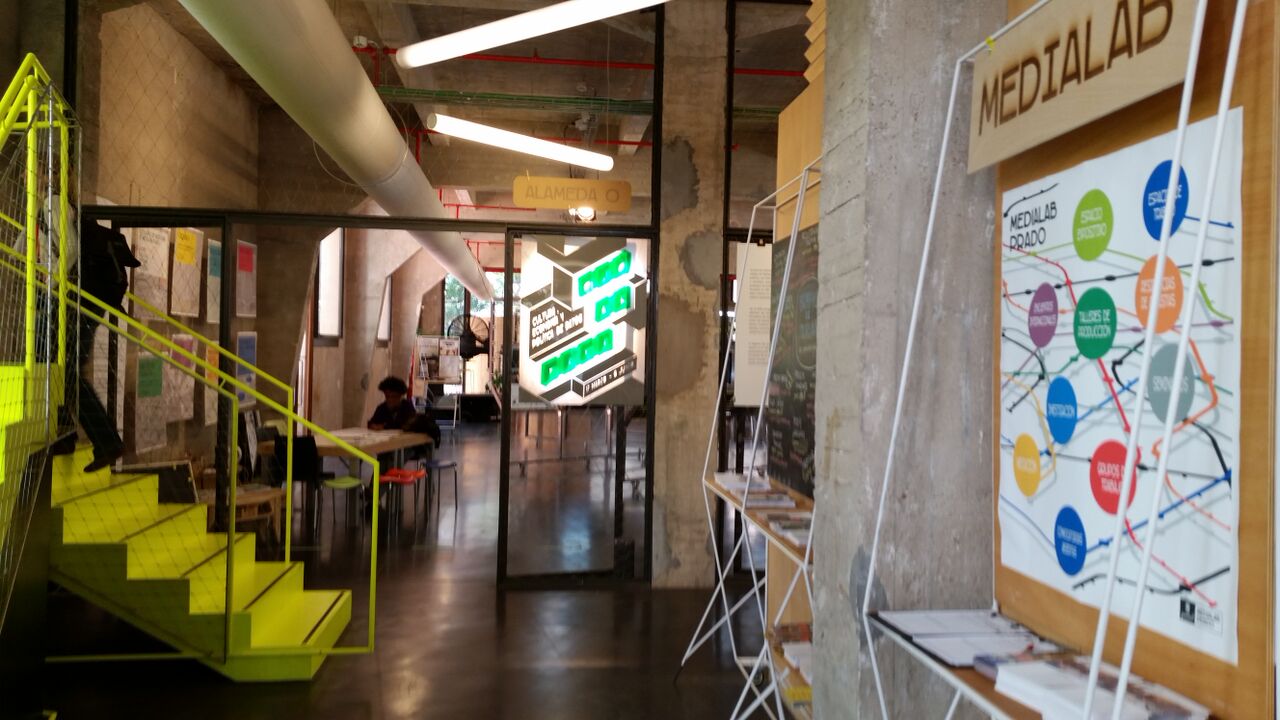

Medialab-Prado is a publicly-funded “citizen laboratory for the production, research and dissemination of cultural projects that explore collaborative forms of experimentation and learning that have emerged from digital networks.”

Medialab-Prado is a publicly-funded “citizen laboratory for the production, research and dissemination of cultural projects that explore collaborative forms of experimentation and learning that have emerged from digital networks.”

And it’s a beautiful space, too 🙂

Given that frame of the workshop was ‘Commoning Data,’ I felt like this was an invitation I shouldn’t pass up.

We’ve occasionally referred to the commons in the course of our work — most prominently in my essay in Code for America’s Beyond Transparency, ‘Towards a Community Data Commons’ (which, in a way, ignited the Open Referral initiative itself). In that essay, I discuss how the true meaning of the commons reaches far beyond — and, I believe, sometimes even belies — the typical usage that’s now associated with ‘open data’ and the internet at large.

All too often, people use the commons to refer broadly to ‘stuff that’s free and open for anyone to use.’ This is reductive, and sometimes even outright wrong.

I much prefer David Bollier’s description:

[T]he commons arises whenever a given community decides it wishes to manage a resource in a collective manner, with special regard for equitable access, use and sustainability.

Towards that end, the ‘Commoning Data’ workshop asked its participants to explore not just the supply of and demand for open data, but also, beyond that, the development of collective capacities for curation, validation, and stewardship of open data as a shared resource — one that must be deliberately cultivated in order to realize its promise as the constructive material for the digital infrastructure of a truly democratic civic society.

I believe that this frame brings our own dilemma of community resource directory data into clearer focus. Here’s a video of my talk:

(If the video above isn’t appearing for you, try it here on the Medialab-Prado website.)

After my talk, during discussions with the leadership of Medialab-Prado and other workshop participants, a number of people said to me something like: “Your talk was interesting, but I don’t think we have this problem in Spain. If we need help, either we go to our doctor or to the Administration [the municipal government office] — they can just connect us to anything.”

It does seem like the service sectors in Spain are mostly organized around the state, with (broadly speaking) health services provided by regional government and human services provided by municipalities.

Surely enough, however, once we ventured outside of the Medialab to discuss with people in the field, the familiar problems emerged.

Many services are provided by many different government agencies, and even government staff find it challenging to know what is happening where.

Spain even has numbers for non-emergency assistance — most prominently 010 in municipalities and 012 in regions, similar to North America’s 3-1-1s and 2-1-1s — as well as specialized assistance lines such as 016 for survivors of domestic violence. People I spoke with reported decidedly mixed experiences in terms of the ability for information to travel effectively among these call-center services.

Meanwhile, services for marginalized populations — undocumented immigrants, elderly, homeless, mentally ill — are increasingly provided by non-profit organizations, which lack any reliable means of sharing directory information. During a couple of visits to the Fundación San Martin de Porres, I heard their staff describe various service directory projects that they have struggled to implement (such as the ‘Recursos’ page of a public-facing homelessness website, Noticiaspsh.org).

Meanwhile, services for marginalized populations — undocumented immigrants, elderly, homeless, mentally ill — are increasingly provided by non-profit organizations, which lack any reliable means of sharing directory information. During a couple of visits to the Fundación San Martin de Porres, I heard their staff describe various service directory projects that they have struggled to implement (such as the ‘Recursos’ page of a public-facing homelessness website, Noticiaspsh.org).

(When I relayed these results to some of the participants who had expressed doubts about whether this is really a problem in Spain, one replied: “huh, perhaps this just shows how ‘W.E.I.R.D.’ we really are” — referencing the acronym of ‘white educated industrialized rich and democratic’ from a recent paper about the biases of people in Western countries who participate in research, policymaking, etc.)

The Commoning Data workshop ran two full weeks (though I was only able to stay for the first couple of days). At the start of the workshop, people self-organized into different projects — including the ‘CityAPI’ group, which was focused upon making data from Madrid’s Open Data Portal accessible via API. Within the CityAPI group, Amanda Sorribes (a PhD student in quantitative neuroscience who came to the workshop hoping to put her data crunching skills to use for the greater good of society) decided to explore the community resource directory data problem.

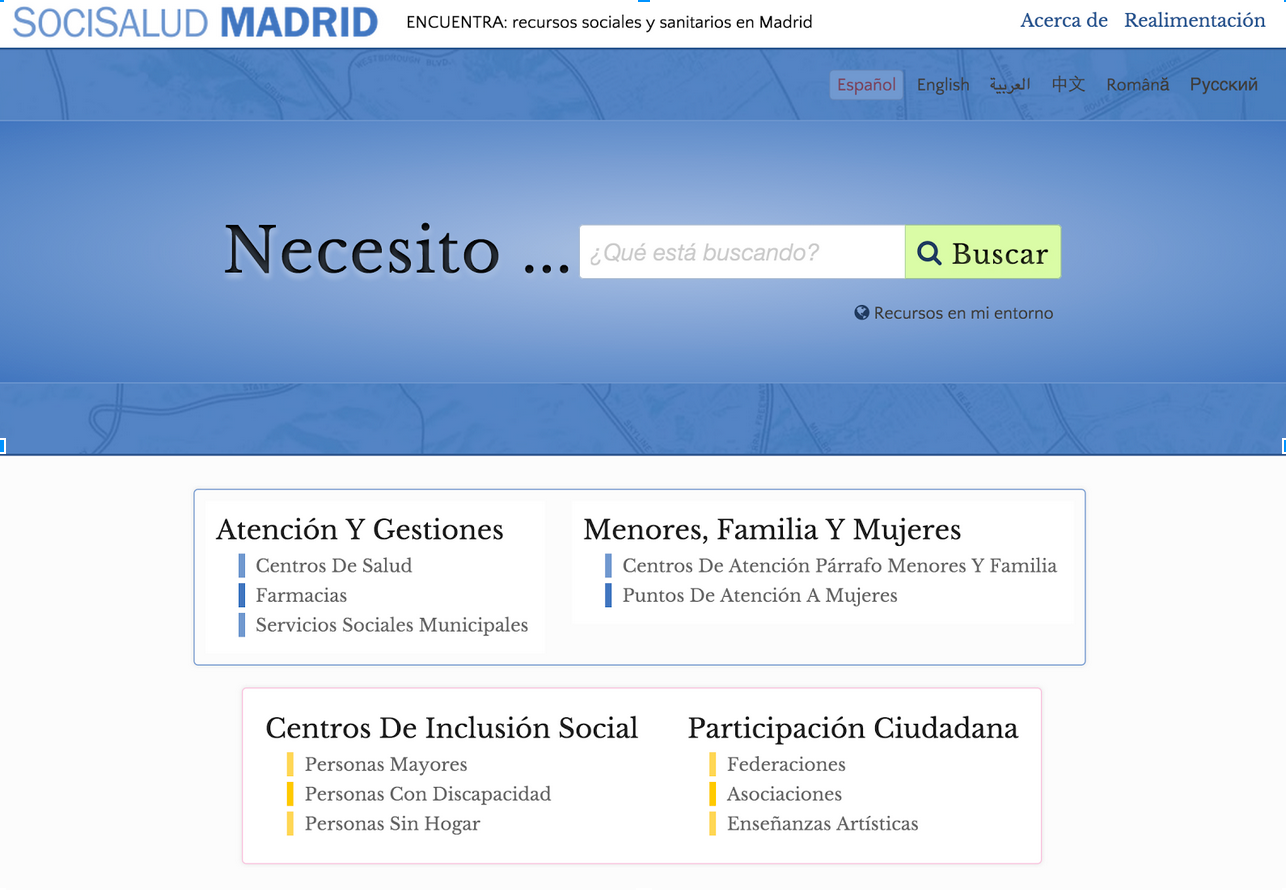

After spending just a couple of minutes on Madrid’s open data portal, we found what we were looking for: quick searches for ‘recursos’ and ‘servicios’ (Spanish for resources and services) turned up a number of directory datasets that appeared to be clean and complete. Over the course of the rest of the workshop, Amanda — along with other Medialab-Prado collaborators including Adolfo Antón Bravo, Gabriel Lucas, Álvaro Santamaría, and Lorena Ruiz — managed to translate the Open Referral format and Ohana API, convert several directory datasets into the former and load them into the latter, deploy the Ohana Web Search front-end, and customize it for Madrid.

And so, an Open Referral demonstration emerged in Spain!

The excellent work done by Amanda and her collaborators, of course, amounts to only the first step in what will be a long path towards a robust resource directory ecosystem. The ‘SociSalud Madrid’ website, frankly, is unlikely to solve anyone’s problems just yet; it merely provides us with a glimpse of possibility for new kinds of solutions.

Many issues have yet to be explored: what is the government’s plan for maintaining those directory datasets on its Open Data Portal? Are there important services that haven’t been published on the portal, or perhaps aren’t even being monitored by the government? How can publicly-funded services be aggregated alongside data about non-profit services? How could regular users suggest corrections and additions to this information? Who should be responsible for stewarding these data resources over time? These are just some of the questions that must be addressed in the process of ‘commoning’ this critical data.

Medialab-Prado is an ideal site to initiate this inquiry. I look forward to hearing about their progress in the near future!

Leave a Reply