I’ve had the honor and privilege of working with the Michigan Community Information Exchange Task Force over the past year. I encourage you to read the Task Force’s final report, which is published here. You can also watch this webinar summarizing the report with commentary from a range of task force members.

In my (admittedly biased) opinion, this is the most thorough articulation I’ve yet seen of a strategy for development of statewide Community Information Exchange (CIE) capacities. I think readers will find that this strategy reflects and elaborates upon the guidance put forth by the social care information exchange “toolkit” published earlier this year by the HHS office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology.

It’s a long video and an even longer document, so I’d like to provide my own personal recap of the CIE Task Force here, and will summarize the recommendations in a following post. (For those who want to go to the source: the report’s key conclusions are summarized on page 8, and the analysis that informed each of those conclusions begins on page 40.)

Let’s dig in!

Background on the Michigan CIE Task Force

As far as I can tell, well before this CIE Task Force was formed, Michigan’s health information technology sector has been at the leading edge of the United States. Earlier this year, with funding from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the state’s Health Information Exchange (MiHIN) elicited an ‘interoperability pledge’ from a range of software vendors who serve overlapping communities in Michigan. This amounts to a significant act of leadership with tremendous potential ramifications for the entire nation.

Likewise, the 2-1-1 Michigan network has demonstrated similarly transformative leadership has in the social care sector. This statewide community resource referral system has already implemented both resource data exchange and cross-platform referral functionality – as recently featured on this blog.

The state of Michigan also has had some success in developing local organizations’ capacity to actively bridge health and human service sectors – through intermediaries sometimes referred to as “accountable communities of health,” and known in Michigan as Regional Health Collaboratives.

This is all reflected in the “Bridge to Better Health” Roadmap, put forth by the state’s Health Information Technology (HIT) Commission in 2022, to promote health equity through active engagement of human service sector partners in efforts to address Michigan residents’ social needs. One of the HIT Commission’s primary recommendations toward this end was the formation of a Task Force to assess challenges and opportunities for Community Information Exchange – and make recommendations for a statewide CIE strategy to the Commission and the state government.

The Task Force consisted of organizational leaders and social care practitioners from across the state, each of whom dedicated hours every month to learn from each other while representing the perspectives of their community in deliberation. We met monthly, and in between these meetings we shared materials, engaged in one-on-one or small group dialogues, and polled members to understand their positions on increasingly nuanced matters. (You can review the entire set of our notes, meeting by meeting, through the history on this Miro board.)

Defining “Community Information Exchange”: what is the problem we’re trying to solve?

As with other communities such as Utah, I proposed to the Task Force that one of its first steps should simply establish a shared understanding of what we mean when we talk about “community information exchange.”

In healthcare, the concept of Health Information Exchanges is relatively well-understood: HIEs are infrastructure for data exchange *among* the many different electronic medical record systems in use across a region or state.

In the context of social care, 2-1-1 San Diego has set a similar precedent for “Community Information Exchange” through useful guidance to help communities build upon its successful precedent for facilitating integration among networks of organizations that use different technologies.

Yet somehow a certain amount of confusion has emerged around the concept of “Community Information Exchange.” At least one CIE Task Force member asked early on whether we should just assess different software vendors and recommend “a single centralized statewide referral platform” that all social care providers would be expected to adopt.

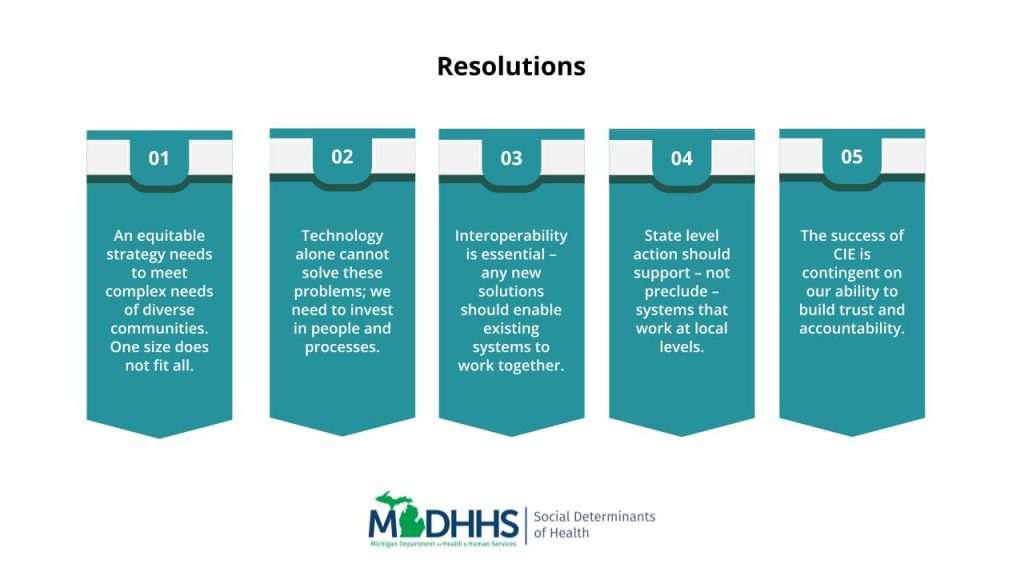

So we reviewed available research on these “single software solutions” – and we found clear indication that this strategy doesn’t seem to be working. Analyzing a range of reports from across the country about implementations of “resource referral platforms” – such as the Trenton HARP initiative and HealthierHere’s platform deployment debrief, as well as the Data.org ReCODE report – we found consistent patterns that are summarized on page 23 of the Task Force report. I will further distill these findings here:

- Few community organizations appear to be interested in using “closed loop referral” platforms, and those that are tend to report that they are of limited value;

- Incentives are not naturally aligned: community organizations and healthcare institutions have different business models, different values, and often don’t trust each other;

- “Closed loop referrals” are not an all-encompassing goal: they are not always possible or appropriate (one task force member called this “a two-dimensional idea in a three-dimensional world”); at the same time, attention is needed on other important use cases for coordination among service providers, caregivers, and clients (like document exchange, care team planning, etc).

- Technology is not a solution in and of itself: in fact we observed an abundance of technologies already in use, yet a scarcity of organizational capacities, human capacities, and sectoral capacities that need to be in place for these tools to be used effectively and equitably.

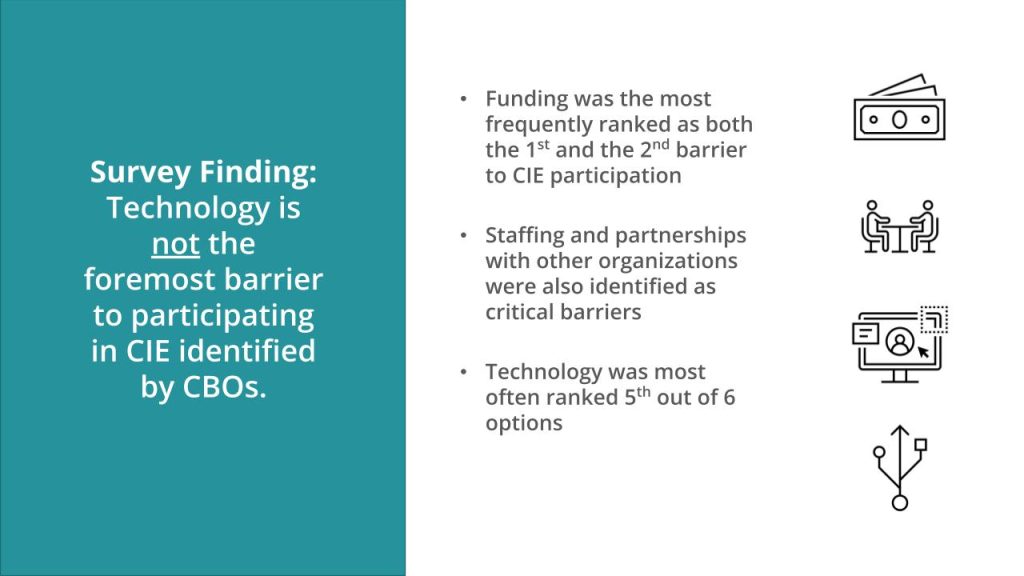

While reviewing these reports from across the country, the Task Force heard similar perspectives from stakeholders throughout Michigan. A survey of over 600 CBOs (633) asked organizations to rank order barriers to participating in CIE – and “technology” was ranked 5th out of 6, with 6 being the write-in option.

We also received presentations by a series of representatives from a range of community information exchange initiatives that are already in various stages of development locally, regionally, and statewide in Michigan. For instance, the MiBridges portal is a nationally-renowned innovation offering integrated access to public benefits and services in a single government website. Meanwhile, the United Way of Southeast Michigan’s Community Information Exchange is already one of the country’s leading local CIE efforts. In light of presentations from representatives of these projects to the Task Force, it became apparent that any effort to develop a new “single centralized system” would pit different communities against each other – and, ultimately, exacerbate the problem that we intended solve.

Not only does this concept of a “single software solution” break with the precedent set by Health Information Exchanges; it puts the onus of change on community-based organizations in ways that are hard to imagine anyone expecting of hospitals or managed care organizations.

Through this analysis, the Task Force collectively affirmed that the intended result of a CIE strategy is to enable coordination among organizations that use different information systems. The Task Force’s problem statement observes that today such systems ”do not share information easily, resulting in redundant processes for service users, duplicated efforts for service providers, barriers to critical resources, and gaps in service delivery.” The purpose of a CIE is to improve health and well-being by making it easier for different service providers using different tools to work together as part of an ecosystem.

Like a Health Information Exchange – but for community-based organizations.

I wish it hadn’t required several meetings (and, here, almost seven hundred words) to clarify this point, yet it turned out to be a crucial part of our process. So I hope other communities can leverage this experience to guide their own efforts.

Understanding users’ needs: shared goals, but different objectives

In the first Task Force meeting, we asked each participant to offer up a set of questions that they wanted this group to answer together. A clear theme emerged:

How can a single statewide CIE strategy equitably serve the varied interests of various impacted parties in diverse cultures across vastly different geographies?

We spent the next couple of meetings analyzing the needs of these various groups of impacted parties – to understand what they need, what success would look like for them, and what kinds of risks of undesirable consequences might by posed by well-intentioned interventions.

We identified the following (very broad) groups of parties who would be impacted by Community Information Exchange:

- Individuals and families in need

- Community organizations who provide services to people in need

- Communities as a whole

- Healthcare institutions

- Government agencies

Through months of Task Force deliberation, we observed that these groups do share common interests – but those interests are not necessarily in natural alignment. For instance, healthcare institutions want more data to inform more decisions about patient care; but it’s often in the interests of social care providers and clients to minimize the amount of data that they have to provide. Meanwhile, community-organizations are already overwhelmed and under-resourced, so receiving more referrals doesn’t necessarily help them – and expectations that they should “close the loop” might actually present CBOs with more costs and liabilities than motivating benefits.

We applied multiple methods to develop this analysis in more detail – such as use cases contributed by Task Force members (see Appendix E of the final report, page 99). Further findings from our comparative analysis about the different needs, success criteria, and risks experienced by different groups of impacted parties begin on page 28.

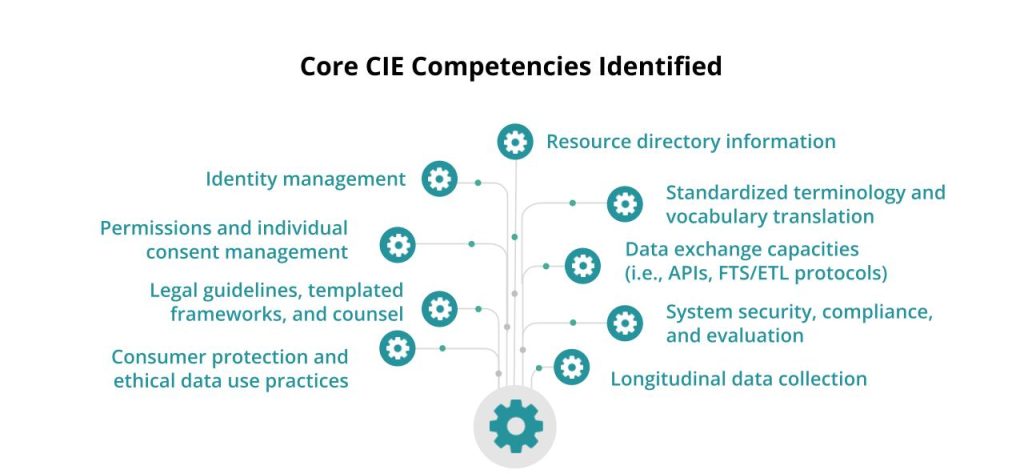

With this analysis on the table, we then articulated the following capacities that needed to align these incentives and address this diversity of needs:

- Different users of different technology systems need access to the same reliable information about the availability of community resources. (This was, in fact, the need most commonly identified by task force members!)

- Service providers and help-seekers need secure, reliable, and accountable means for unique identification of individuals across different technology systems. (Thanks to Alana Kalinowski of 2-1-1 San Diego for specifically calling attention to the statewide nature of this challenge.)

- Community organizations, government agencies, and healthcare providers need secure, vendor-neutral methods of cross-system exchange of data about a person’s needs, their care activities, and outcomes. (As mentioned before, MiHIN has already elicited a commitment to adopting such standards from a broad range of social care tech providers.)

- Communities, governments, and health and social care organizations need aggregated data for longitudinal analysis that can inform their understanding of community needs, program effectiveness, etc.

- All impacted parties need workable legal agreements to stipulate the terms of data exchange across different technology systems.

- Service providers, their clients, and communities at large need a shared ethical framework to ensure equitable outcomes from this work.

- Community organizations need capacity (i.e. funding, human resources, and institutional processes) to do this work.

In summary, the Task Force agreed that a Community Information Exchange strategy must use a variety of tactics to promote multiple kinds of interoperability: technical interoperability to make data exchange possible, organizational interoperability to make data exchange useful, and human interoperability to make it actually happen. Furthermore, the Task Force agreed that though such interoperability is a necessary condition to achieve our intended result, it is not in and of itself a sufficient condition. If we want social care providers to do more work – to serve more people, collect more data about them, and engage in more work to coordinate with other providers and these systems themselves – we are going to have to change how services are funded. If we want data exchange to result in equitable outcomes, we are going to have to make ongoing distinctions between what can happen and what ought to happen. And all of that means we are going to need new systems for making decisions together.

The Michigan CIE Task Force Report puts forth a range of recommendations as to how those systems should work and how they might be resourced. But this blog post is quite long enough! Stay tuned for the rest of the story.

For now, in addition to the Report and Webinar linked above, I encourage anyone who’s read this far to check our work: the version history of this Miro board contains aggregated notes from each stage of this process.

I also want to express gratitude for the facilitation frameworks that I drew upon to guide the design of this process: Eugene Eric Kim’s Faster Than 20 collaboration tools, David Sloan Wilson’s Prosocial framework for group deliberation, adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy, and Sasha Costanza-Chock’s Design Justice.

Leave a Reply