In late September I had the privilege to discuss our work at the Data for Good Exchange, a symposium hosted by Bloomberg.

As part of the event, I presented a paper which you can read here.

Much of the paper recaps the thinking and work behind the Open Referral initiative to date. It traces our analysis of the ‘community resource directory data problem.’ Then it describes the steps we’ve taken so far: the publication of our Human Services Data Specification (HSDS) — an ‘interlingua’ data exchange format that enables any directory information system to share resource data with any other system that helps people navigate the human service sectors — as well as the development and redeployment of the Ohana API — an ‘open platform’ that can distribute resource data from one point to many external tools.

Then, taking into account some of the lessons we’ve learned over the past year, I editorialize a bit. Here’s the key part:

The pathway to broad adoption of an open standard such as HSDS is likely to require the provision of tools that enable distributed actors to cooperate in the aggregation and validation of community resource directory data.

The remainder of the paper sketches out just such a goal for the next phase of Open Referral.

§

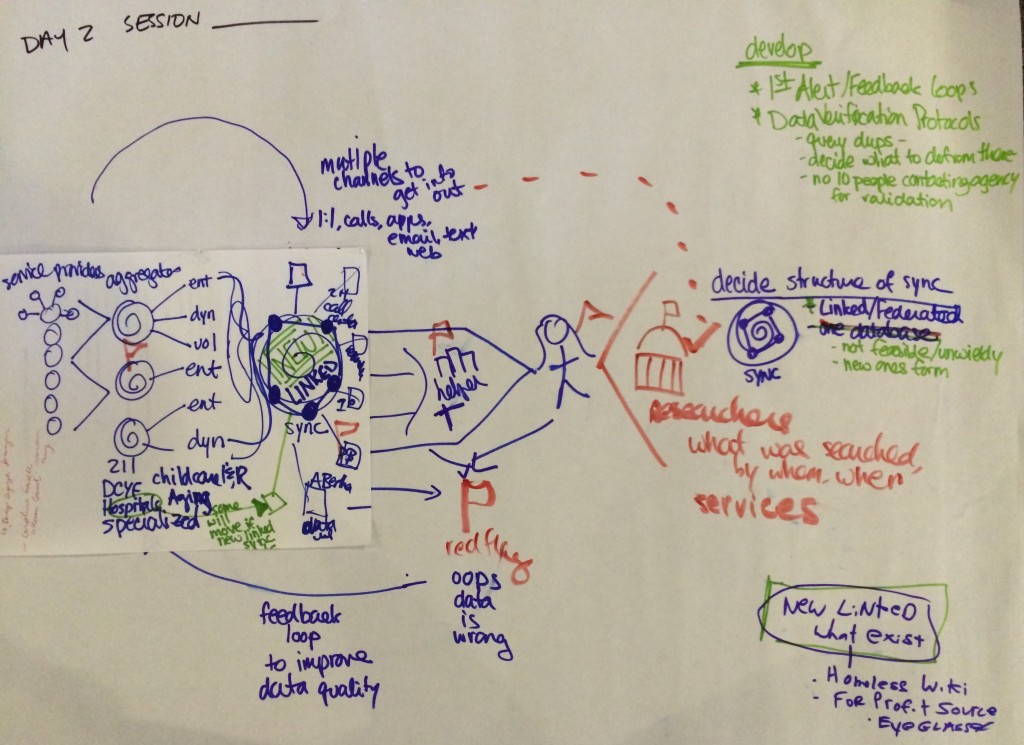

We’ve long recognized the need for tools that enable distributed actors to cooperate around the maintenance of resource data (as articulated by the stakeholders at last year’s Open Referral workshop).

Now, through the course of experimentation with HSDS and Ohana, a vision is coming into focus of what we may need to build next, which I describe as a ‘federated publishing platform.’

I use the word ‘federated’ in pointed contrast to a concept that may be more familiar: a “centralized database,” a “one-stop shop,” “clearinghouse,” etc.[1]

Some variant thereof is often proposed in this field — yet rarely, if ever, achieved. The notion implicit in the ‘centralized database’ idea is that if everyone could use the same system, it would be much easier to both maintain and find resource data. One of the main problems with this theory is that its success is contingent upon ‘everyone’ actually being both able and willing to adopt an entirely new system. This has proven to be an unlikely scenario. Humans tend to dislike change, and this is even more true for institutions. Furthermore, the value proposition of a centralized database has the added disadvantage of not possibly being user-centered around the particular needs of each of a community’s diverse stakeholders. While a centralized solution might hypothetically be better for everyone in a world where everyone else used it, in the real world the prospect poses enough uncertainty and limitations for participants that few (if any) reach the critical mass necessary for such success.

Code for America’s Ohana Project has demonstrated a new way for a ‘centralized’ system to potentially meet “everyone’s” needs. When resource directory data is available via an ‘open API,’ others can build tools that use this data to their particular purposes, such as the Ohana SMS app and the Logic Library projects in D.C., and mRelief and the Chicago Health Atlas in Chicago.

However, in our actually-existing decentralized world, in which many different directories already exist to meet various needs, competing for attention and resources along the way, we’ve observed that technology like Ohana still doesn’t help people answer the big hard operational question that has always faced community resource directories: ‘How are we going to keep this database up to date?’

On that point, just a bit more editorializing from the paper:

Human service sectors are fundamentally distributed; the means of producing and circulating data about them may need to reflect this reality… [I]n most circumstances, a single entity cannot (and perhaps should not) unilaterally control the means of production and publication of community resource data. In other words, this is a many-to-many problem for which we need many-to-many solutions.

Toward this end, I believe we should explore the prospect of ‘database federation.’ Federation entails a system of interconnected systems; each individual system retains autonomy even while they integrate with each other as constituent parts of a coherent whole. Different users can use different information systems that all share access to the same data.

This is not a new concept, not even in the world of ‘information and referral.’ In fact, we’ve learned about it from our neighbors in Ontario, where Ontario 211 stewards a system that aggregates data across a province-wide network, consisting of dozens of local referral providers who each maintain their own resource directories, while software used by the Community Information Online Consortium enables the assignment of different records to different agencies and the circulation of feedback about accuracy of records shared by multiple agencies.

§

I’ve heard various proposals for the kind of technology that would make up a ‘federated publishing platform.’ It may not entail building anything from scratch, but rather applying already-existing tools to this particular problem.[2] Personally, I’m agnostic about such details. It seems to me that the important thing is to test as rapidly and soundly as possible my hypothesis regarding the core design objectives:

1) Aggregation of resource data from some set of distributed sources — such as government open data portals, compliant community resource directories, agency websites, user-generated feedback, Google Places, etc.

2) Facilitation of trustworthy record verification — so that out-of-date, incomplete, and conflicting resource directory records are brought to the attention of humans who can efficiently and reliably check their accuracy.

3) Republication of interoperable data to third party systems — so that directory information, once verified, could be used many times by many tools.

So there is the ‘why’ and the ‘what.’ [3] We still need to answer questions about ‘who,’ ‘where’ and ‘how’ we will build the first open source instance of such infrastructure. Suffice it here to say that the answer to these questions will have to come from people first, rather than data or apps. We’ll consider this challenge more directly in 2016.

Thanks to Arnaud Sahuguet and the Bloomberg Data for Good Exchange team for a great event and opportunity.

§

[1] More recently, the popular shorthand is ‘the Yelp for Social Services.’

[2] In the paper, I observe that precedents for such technology already exist, through platforms such as Github and WikiData, and protocols such as PubSubHubbub — as well as nascent technologies such as Dat.

[3] The paper also suggests “what functionality such infrastructure would not include.” Specifically, I hypothesize that a federated publishing platform should not be designed to enable the curation of information about human services, nor collection of feedback about the quality of services. Curation and feedback collection absolutely should happen — yet they probably need to happen in different ways, through various applications that people use to find what they need. This is to say, a federated platform would establish a marketplace in which distributed actors cooperate with each other around maintenance of directory data (a problem that they all share), in order for each to focus more fully on using this public information in whatever ways best meet the needs of their particular users.

Leave a Reply