[David Poms is a policy analyst for the DC Primary Care Association, and a coordinator of the DC-PACT (Positive Accountable Community Transformation) collective impact coalition. Welcome, David!]

The District of Columbia’s community of health, human, and social service providers are struggling with a familiar challenge: they want to be able to more effectively coordinate care among their patients and clients, yet their systems can’t currently ‘talk’ to each other.

In response to this issue, DC’s Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) initiated the DC Community Resource Information Exchange (DC CoRIE) to develop data infrastructure that supports coordinated screening, referral and tracking across a range of health, human, and social services in DC. DHCF selected the DC Primary Care Association (DCPCA) and Open Referral to lead an initial planning phase to help understand how to build infrastructure that would facilitate these functions. As part of this planning phase, we were tasked with the development of a Community Resource Inventory that can sustainably aggregate up-to-date information about the health, human, and social services available to DC residents.

DCPCA was selected to lead this initiative thanks to its work facilitating the DC PACT coalition, a collective impact initiative of health, social, and public service organizations focused on addressing health related social needs and health equity by improving cross-sector alignment. DC PACT (Positive Accountable Community Transformation) has consistently identified the need for a sustainable and trustworthy community resource inventory (CRI) to support this work.

Open Referral led the process of developing the CRI infrastructure, and researching the various needs and opportunities that can guide the scaling and sustainability of this infrastructure.

Toward that end, we designed and facilitated a participatory process that sought to learn from, align with, and offer support to those resource referral efforts which already exist in DC. We began with a landscape assessment and data analysis of already-existing resource directories, and conducted a series of interviews with stakeholders involved in the production and use of those directories.

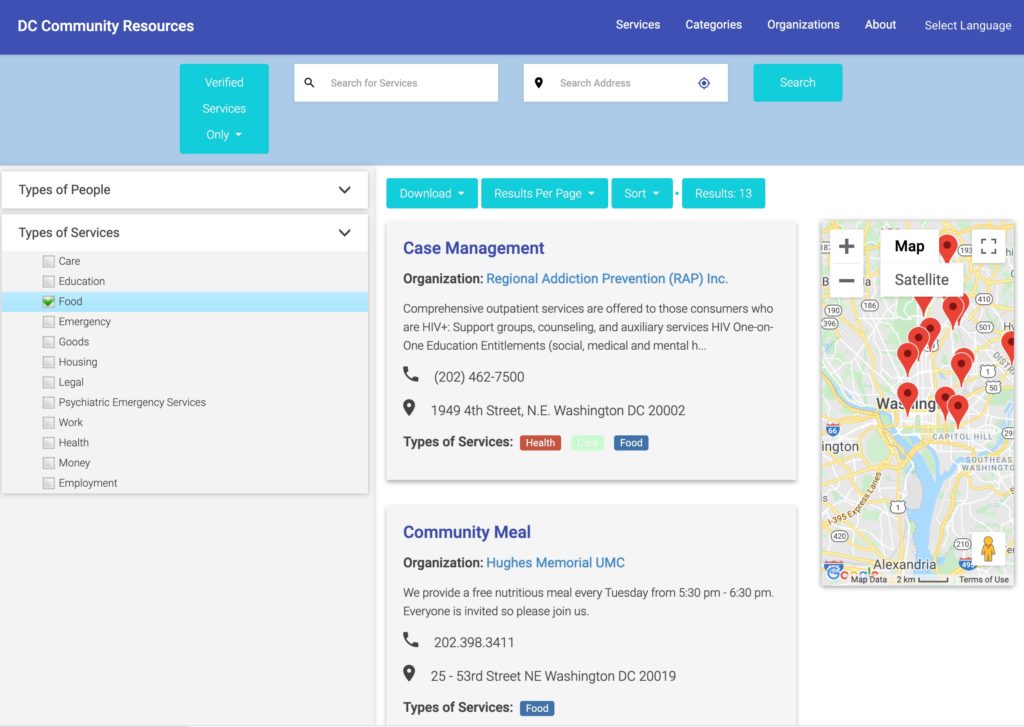

Along the way, we also built an open resource database that publishes data in the standardized Open Referral format. This system serves as a live demonstration of open, standardized resource data infrastructure – and a foundation for future development.

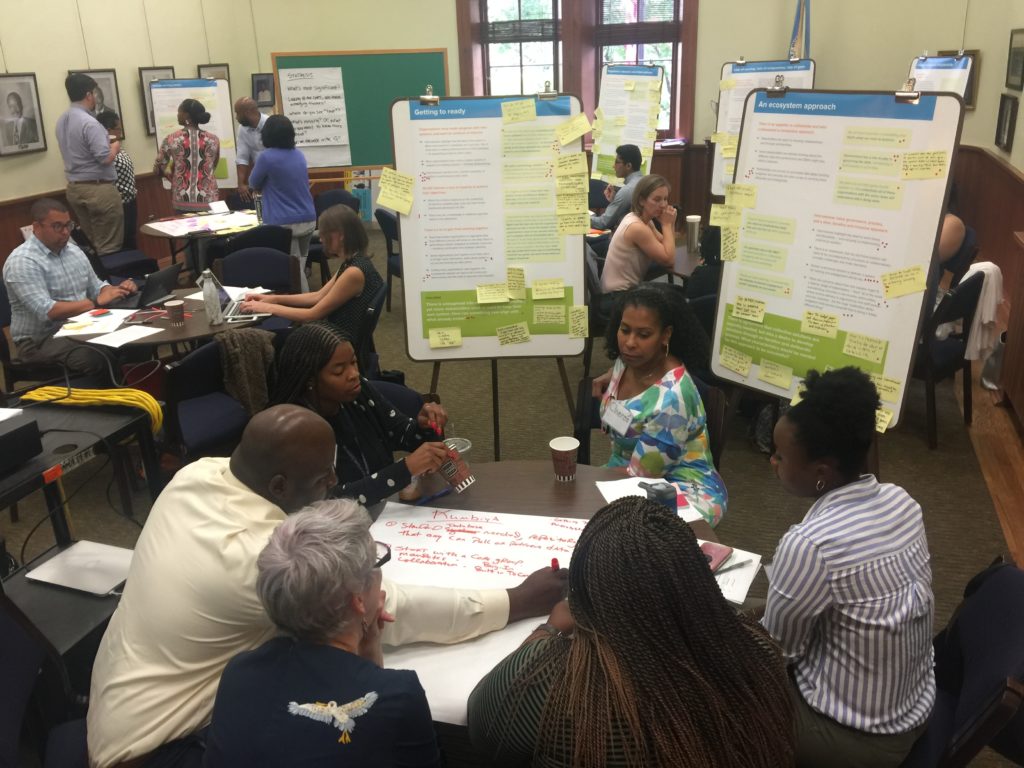

We synthesized our findings, convened these stakeholders to review this analysis, and finally compiled their feedback into a set of recommendations as to how District stakeholders might develop and sustain shared resource directory infrastructure.

The Final Report for Phase One is here.

Below, we summarize our key findings and proposed strategy.

Envisioning a new system in a world of already-existing systems.

Overall, our research with stakeholders in DC affirmed Open Referral’s core critique:

Resource data is laborious to maintain, and is also used in a diverse range of contexts, by diverse types of users – who have diverse vocabularies and needs — so one tool can’t effectively serve everyone. Instead, many organizations use different tools to collect and share resource data, in accordance with their particular needs. And without the ability to cooperate, they end up struggling to maintain this data themselves.

A common theme rang out in our interviews and the workshop dialogues: stakeholders in DC share a strong interest in cooperating with each other, and they also feel strongly that DC’s service directory information should be publicly available as an ‘open resource’ – yet enough stakeholders want to continue using their own system that the prospect of ‘one centralized database that everyone uses‘ doesn’t seem viable.

As we considered these dilemmas in the stakeholder workshop, our conversation shifted away from the concept of a ‘centralized one-stop-shop,’ to instead consider the prospect of a ‘common core of data’ that could be shared among an open ecosystem of tools and applications.

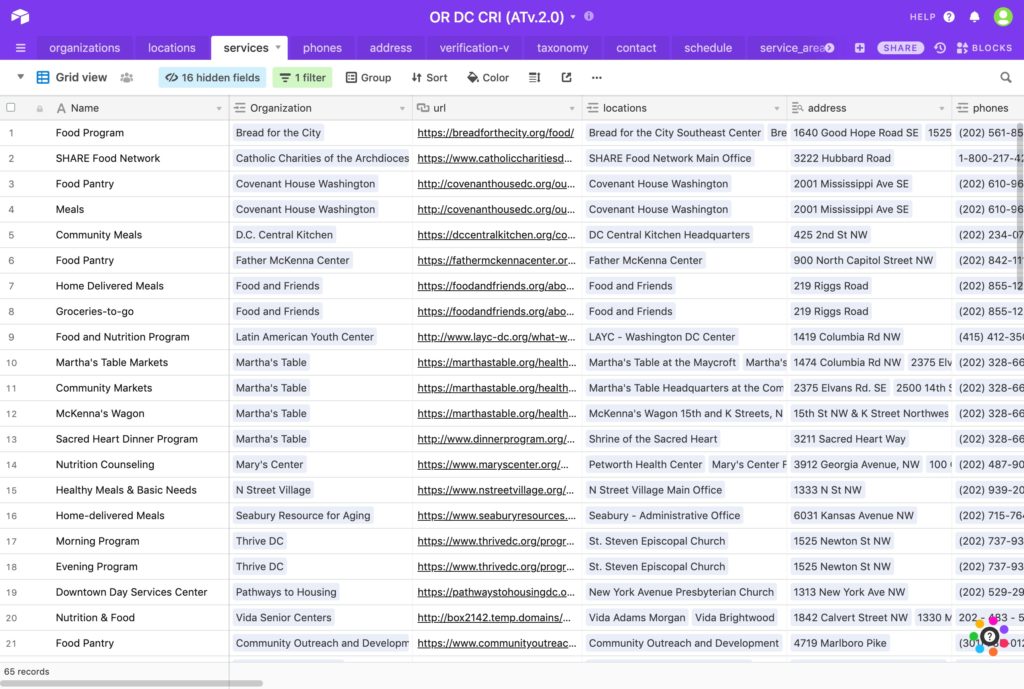

We developed a functional version of this kind of ‘common data pool,’ using the Open Referral Airtable designed by Sarapis. This is a free system (though scaling its use will likely require upgrading to paid features) and it can output resource data in a standardized format, so third party systems can access it and present it to users however they see fit — and even augment it with their own specialized knowledge. The technology we need to do this is already here.

The big question we posed to local stakeholders was: how can this sort of ‘common pool’ of directory data be sustainably maintained as an open resource?

Through dialogue with stakeholders, we developed a strategic framework with several prongs. Here is a summary of our recommendations:

DC should establish a designated steward to serve as a ‘Resource Data Utility.’ This Data Utility (which could be an already-existing organization or a new one formed for the purpose) should be responsible for the maintenance of openly-available resource data about health, human, and social services in DC. The Utility should sustain operations by 1) lowering the costs of resource data maintenance through data partnerships among government agencies and other referral providers, while 2) generating revenue from “service-level guarantees” and “premium features.”

Read the full set of recommendations here.

Let’s unpack this sustainability strategy below.

Lowering costs through data partnerships

Our research found that DC has roughly 500 organizations providing roughly 1,500 services — and that roughly two full-time employees (or the equivalent) would be needed to ensure that resource records can be reliably updated every six months. However, our research also identified several ways in which these costs might be lowered through data partnerships with key institutions that can (and, in some cases, already do) collect directory information from within their own remit.

Open service registers can aggregate information directly from providers

We roughly estimate that about a quarter of the services available in the District receive funding from about a dozen DC government agencies. Those agencies could play a key role in ensuring that information about such services is accessible and accurate. For example, these agencies could establish official registers of the services provided by their grantees and/or contractors.

A Register is an official list — and, crucially, an accurate list.

As the Open Data Institute explains, digital registries can dramatically reduce the cost of data management and associated service delivery – providing machine-readable, canonical sources of truth – though they require collaboration to develop and maintain over time.

We already found at least one example of a service registry in development in DC: the DC Department of Human Services, for instance, is already using the Open Referral format to develop an open register of all services in DC’s Continuum of Care (i.e. services for people experiencing homelessness). Once aggregated as open data, this register can be shared simultaneously among many systems.

A Data Utility could decrease the cost of service directory data maintenance by partnering with other institutions that fund services — other government agencies and even philanthropies — to establish interoperable service registers, in which recipients of grants and/or contracts would be required to keep information about their own services updated themselves. (The Data Utility might even generate revenue by contracting with such agencies to design, deploy, and/or monitor the accuracy of these registers.)

Network institutions can aggregate information from specific domains

The Data Utility can also reduce costs of data maintenance by partnering with network institutions that have formal relationships with service providers in a given domain.

Our research found a range of network institutions that provide formal support for entire service subdomains — like the Capital Area Food Bank for food pantries; the DC Bar Pro Bono Program for legal aid; the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council for re-entry services; and so on.

These institutions often already keep track of the service providers in their domain — providers with whom they often already have a formal relationship — which means they are positioned to be trusted stewards of these domains, sharing this responsibility (and the associated data) with the Data Utility.

We estimate that already-existing, domain-specific resource directory maintainers in DC might be able to contribute as much as half or more of the contents of a resource inventory (reducing maintenance costs substantially), simply by adopting new methods of collecting and publishing information that they are already committed to maintain.

Generating Revenue by Providing Resource Data As A Service

Our research suggests that a Resource Data Utility could recoup most (if not all) of the costs of maintaining and publishing open data by generating revenue for services associated with that data.

For example, a Data Utility can monetize guaranteed levels of ‘Resource Data As A Service’

Through dialogue with vendors and community anchor institutions, we’ve found that while open data may be free, any institution that might operationalize the use of that data is likely to need contractual guarantees as to various criteria of data quality and delivery. This means a Data Utility can publish open data while charging (reasonable) fees for “Service-Level Agreements” pertaining to that data.

Such ‘levels of service’ might include:

- Reliable maintenance of resource data (perhaps at higher frequencies and/or with more granularity than the default).

- High-volume API access, at virtually-constant uptime.

- Prioritized responses to requests for correction.

- Technical support.

This opportunity is most clearly apparent when it comes to the various ‘care coordination’ platforms offered by software vendors that are already in use within the District. Currently, these platforms pass the costs of resource data maintenance off onto their users; they could, instead, pay the ‘Data Utility’ to provide a regularly-updated, ubiquitously-available feed of resource data. (We roughly estimate that a basic SLA might be worth $3,000 to $5,000 a month — less than what it would cost these organizations to maintain such data themselves — and, if pooled across a market of at least half a dozen software vendors, this might amount to half or more of the maintenance cost of the Resource Inventory.)

A Data Utility can also offer premium features that add value to open resource data

Beyond basic ‘service level agreements,’ the Data Utility can also generate revenue from fees for features that add value to the basic “raw” open data. For example, the Utility could offer:

- customizable “white-labeled” websites with specific geographical and/or topical focus.

- metadata to improve search results and matching algorithms.

- customizable category management tools.

- specialized resource information that falls beyond core standards.

We also know that technology and data is only a tool, and people need training and support to use it effectively. To various institutions that might use the resource data that it maintains, the Data Utility can offer valuable consulting services such as:

- Hands-on training in screening, resource navigation, and referral

- User research and user experience design

- Evaluation and quality assurance

Finally, when a Data Utility’s infrastructure is fully operational – and used by the various institutions outlined above – the Utility can offer at least one more set of services that can generate sustaining revenue: intelligence about the health, human, and social service sectors.

If the Data Utility becomes essential infrastructure for an ecosystem of third party tools and applications, it can also monitor traffic across that ecosystem. The Utility can produce cross-channel analytics about patterns of searches, clicks, and other data about the use of resource data. These analytics can be synthesized into needs assessments and other business intelligence valued by local institutions, from governments, to universities, to philanthropies, to healthcare payers, etc. By becoming the canonical source of data that “everyone” uses, the Data Utility can become an indispensable source of intelligence about the operations of DC’s health, human, and social service sectors, and the health of its communities — and some of that intelligence can generate revenue that sustains the Utility’s operation.

Governing this resource data infrastructure

The sustainability model described above — developing partnerships to facilitate resource data supply, and generating revenue for premium services to institutional users of resource data — would involve a lot of moving pieces, and require the active participation of various types of stakeholders. In our recommendations, we also proposed a governance model that can coordinate the activities of responsible and equitable stewardship.

A Data Federation to facilitate participation and oversight

In a ‘data federation,’ responsibilities and privileges pertaining to resource data maintenance and use can be jointly established among stakeholding institutions. In this concept, a ‘Data Utility’ would be a designated steward that is accountable to the Data Federation membership.

When it comes to the Data Utility itself, we did not go so far as to recommend a specific organization, or even a particular type of organization. A range of non-profit organizations and for-profit companies already maintain resource directories in DC (however, it’s worth noting that none of the stakeholders we interviewed voiced confidence that any of these directories are comprehensive and up-to-date). With cooperative efforts to build their capacity to publish open data, several of these organizations might plausibly serve the role of Data Utility; success may hinge much less on the type of organization than the design of its relationship to the Data Federation.

A Data Trust to steward assets and enforce rules

One new idea emerged through the course of our research and deliberation: a ‘data trust’ could hold the resource directory data – and the associated rules and licenses that pertain to its maintenance and use – in a legal entity that is structurally committed to the interests of DC residents.

By placing resource data (and the stewardship thereof) in a Resource Data Trust, stakeholders in DC could disentangle the question of ‘who should be responsible for maintaining resource data’ from the question of ‘who should own the resource data’ – because the resource data would become the collective property of the residents and institutions of DC. One or more third parties could be made responsible (and appropriately compensated) to ensure the work of data maintenance is reliably performed – while the data itself remains an asset to be held and administered in accordance with the interests of DC’s residents and community organizations.

We are excited to explore the potential for this Data Trust concept! (Thanks to Digital Public for their thought leadership and advice regarding data trusts.)

Looking to the future: join us on the road ahead

We’ve been pleased to have had the opportunity to work with the DC Department of Health Care Finance, the DC Primary Care Association, and stakeholders throughout the District on the DC CoRIE project.

Having established the plausibility of open resource inventory infrastructure, stewarded by a Data Utility through a multi-stakeholder Data Federation, we are eager to get to work on developing such institutional capacities.

Open Referral is also eager to work with other communities grappling with these same problems. Reach out if you’re interested in learning more!

§

This pilot project was a true team effort. Open Referral partnered with QRI to manage the process of data acquisition, transformation, and synthesis; Sarapis to develop the Community Resource Inventory and associated tooling; Genevieve Smith and Ariadne Brazo for resource data analysis and verification, respectively; and Loup Design & Innovation for our stakeholder research, workshop, and reporting processes.

Leave a Reply